Dem Governor Signs Controversial Assisted Suicide Law

Delaware’s Democratic Governor Matt Meyer signed a controversial bill into law Tuesday, legalizing physician-assisted suicide for terminally ill patients in the state. The move makes Delaware one of just a handful of states to allow the practice, marking a dramatic shift in end-of-life policy that has divided lawmakers and faith leaders for nearly a decade.

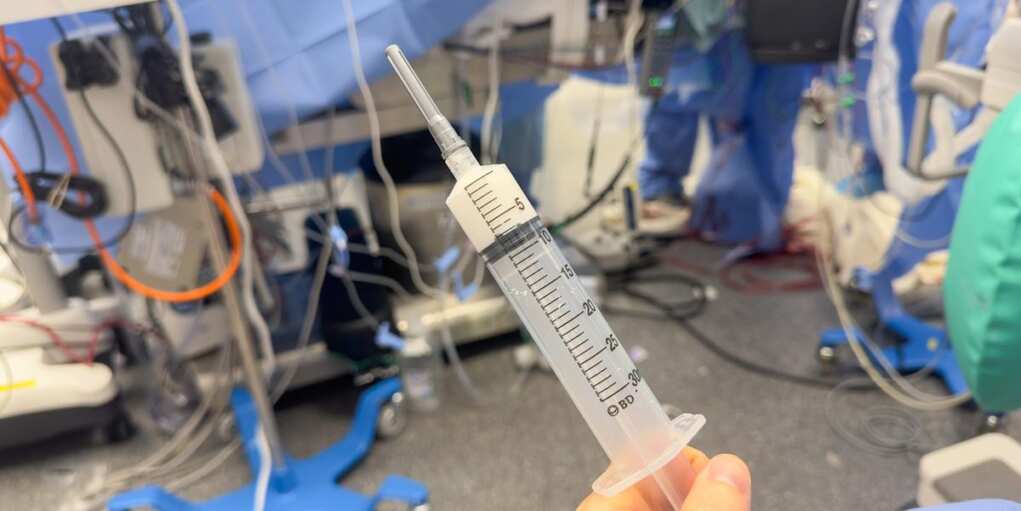

Supporters hailed the bill as a compassionate step toward giving patients control over their final moments. The law permits terminally ill adults, with the approval of two separate medical professionals, to request and self-administer life-ending medication. A series of safeguards—including two verbal requests and one written submission—are intended to prevent abuse, but critics argue the law opens the door to dangerous coercion.

“This signing today is about relieving suffering,” Meyer said during the bill’s signing ceremony, “and giving families the comfort of knowing that their loved one was able to pass on their own terms without unnecessary pain.”

But not everyone sees it that way.

Opponents, including the Catholic Diocese of Wilmington and a coalition of conservative lawmakers, warned the law undermines the sanctity of life and could leave vulnerable patients exposed to pressure, particularly in a health care system increasingly focused on cost containment.

“This bill fundamentally changes how we value life in Delaware,” Bishop William Koenig said in a statement. “The Catholic faith holds that every human life, from conception to natural death, is sacred. That means we do not end suffering by ending life.”

The legislation narrowly passed the Delaware House by a vote of 21-17 and the Senate by 11-8 after nearly a decade of failed attempts. Previous versions of the bill were repeatedly blocked, most recently in 2024 when then-Gov. John Carney, also a Democrat, vetoed the measure over what he called “a lack of firm consensus.”

The new law allows doctors to write prescriptions for life-ending drugs, but only after confirming that a patient has less than six months to live. Patients must be mentally competent and capable of self-administering the medication. Exceptions are made for patients seeking entry for legitimate medical treatment not related to ending life.

While hailed by advocates as “humane and dignified,” the bill has drawn national attention from pro-life organizations, many of which fear it sets a dangerous precedent. Groups have pointed to similar laws in Oregon, Washington, and Canada—where assisted suicide has expanded well beyond the terminally ill—as cautionary tales.

“This is about more than individual choice—it’s about what kind of culture we’re building,” said one Republican state lawmaker, who argued that Delaware should be investing more in palliative care, not offering what he described as “a shortcut to the grave.”

Proponents counter that the law gives peace of mind to patients with no hope of recovery and avoids the agony of prolonged suffering. They also note that several layers of consent are required, making it harder to abuse.

But for religious leaders and some medical professionals, the moral concerns outweigh procedural safeguards.

“There’s a difference between refusing extraordinary treatment and actively ending a life,” Bishop Koenig said. “This bill crosses that line.”

Whether the issue re-emerges in court remains to be seen, but for now, Delaware has joined the growing list of states reshaping the national conversation around end-of-life care.

The law is set to take effect later this year.